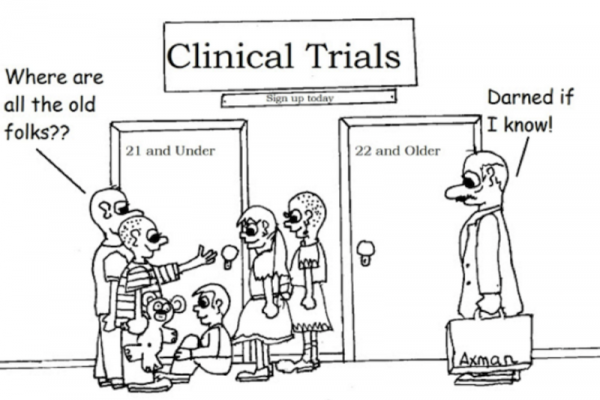

Where Are the Older Volunteers in Clinical Trials?

Clinical trials are conducted for testing the efficacy and safety of a treatment (e.g., medication, device, procedure) for one or more medical conditions. However, older adults are systematically underrepresented in clinical trials, and this creates serious repercussions in the health-care industry.

For example, as early as 1999, a study of Southwest Oncology Group reported that although about 60% of new cases of cancer occur among older adults, they comprise only 25% of participants in cancer clinical trials1.

Besides cancer studies, older adults are also systematically underrepresented in clinical studies on other chronic conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and dementia. In 2004, Schoenmaker and Van Gool reported a wide age gap between the patients enrolled in dementia clinical studies and the patients with dementia in the general patient population2. The dementia patients who are included in clinical research are systematically younger than patients from the general population.

Due to lack of population representativeness, many trials failed to balance the internal validity and the external validity. In the context of clinical research, Internal validity refers to whether the design and execution of the clinical trial leads to valid conclusions about the efficacy and the safety of the treatment.

For example, say you were interested in whether a new drug was effective for headache relief. If you don’t include a control condition, such as a placebo pill, along with the experimental treatment condition, you won’t be able to conclude that the drug is effective. You may be observing a placebo effect, where any treatment would work (e.g., to cure a headache) as long as the patient believed the treatment would relieve pain. So, typically, a trial involves random assignment to a placebo intervention and a treatment intervention as well as trying to keep the patients blind to the intervention that they are in (hence the placebo pill) as well as having the evaluators of the outcome blind to the intervention when they make measurements on the patients (such as for blood glucose levels, HbA1c, in a diabetes trial). If the internal controls are not adequate, then the conclusions about the efficacy of the treatment may not be valid.

External validity refers to the generalizability of the trial. Even when internal validity is strong, if the trial involves just one age group, say college students, would make it difficult to conclude that the treatment effect (assuming it was significant) will generalize to the whole population (e.g., children, seniors).

Often, internal validity and external validity are in conflict as tight internal controls, the inclusion and exclusion criteria for enrolling into a study, systematically bias in the types of sample recruited, making it more difficult to ensure generalizability. You need internal validity to draw valid conclusions about efficacy. You need external validity to draw valid conclusions about the range of people for whom the treatment can be expected to have efficacy.

For example, studies are usually designed to minimize confounding factors and adverse events by excluding patients with co-medications/polypharmacy, multiple comorbidities, and cognitive impairment, which disproportionately exclude older adults. The participants in a trial had fewer comorbid conditions and lower overall mortality than the general patient population3. Stringent eligibility criteria may explicitly or implicitly limit the inclusion of elderly patients with typical age-related organ impairment and comorbid conditions that may not interact with the treatment under study. Moreover, there is a lack of evidence for assessing quality of care for elderly patients with multiple comorbidities as clinical practice guidelines commonly only focus on a single disease. To provide the evidence for assessing the efficacy and safety of a medication that will be used in elders with multiple comorbidities, these patients should be appropriately represented in clinical trials.

What are the consequences?

What are the consequences of ignoring or excluding older adults in clinical trials? First, older adults who cannot afford the treatment may not have a chance to try the free treatment that may save their lives. More importantly, older adults often have more chronic conditions and take more medications than younger people. When they take the drug that was primarily tested on younger people, they may not find it as effective as stated. Even worse, they have a higher likelihood to encounter serious adverse drug reactions such as toxicity, organ damage, or even death due to complex drug-drug interactions.

From 1969 when the drug event reporting system of FDA was initiated till 2002, about 2.3 million case reports of adverse events for the cumulative number of approximately 6,000 marketed drugs were entered in the database4. Out of these 2.3 million cases reports, 1.8 millions reports originated from the United States. Among the reports who specified age, 35% referred to those 60 years or older. More than 75 drugs/drug products have been removed from the market due to safety problems. Since 2006, the number of reports gradually increases each year and has exceeded 1 million in 2013 (See the figure below). This phenomenon naturally makes us to rethink about the clinical research enterprise. How can we identify most safety issues during pre-marketing clinical trials instead of asking the entire real-world patients to “test” the drugs?

How to improve the representation of older adults in clinical trials

Dissemination of information about clinical trials

ClinicalTrials.gov is the official clinical study and results registry created and maintained by the U.S. National Library of Medicine. Mandated by Section 801 of the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA 801), all the US-based clinical trials of drugs, devices, and biological products other than Phase I trials have to be registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. As of October 6, there were 227,255 studies with sites in 191 countries registered. On September 16, FDA released the final rule for clinical trial registration and results information submission in ClinicalTrials.gov. National Institutes of Health Director Dr. Francis Collins co-authored a viewpoint in the Journal of the American Medical Association about recent NIH efforts on clinical trial reform which aim to enhance the award processes, increase NIH’s ability to better assess applications, improve oversight, and increase sharing of results5. Dr. Collins and other senior leaders said: “Investigators and sponsors who fail to comply with the regulation may be subject to civil monetary penalties assessed by FDA. In addition, NIH will withhold clinical trial funding to grantee institutions if the agency is unable to verify adequate registration and results reporting from all trials funded at that institution. The availability of results will promote innovations in clinical trial design and avoid duplication of unsuccessful strategies, thereby avoiding unnecessary risks to research participants.”

With improved transparency of clinical trials, clinical investigators should be able to broaden their search for trial participants. Meanwhile, it should be easier for patients to find clinical trials to get screening.

Relaxing overly-restrictive eligibility criteria in clinical trials

Clinical trial designers should evaluate the population representativeness of eligible patients during the design phase of a new trial. Normally, one could manually identify a set of representative exclusion criteria in a trial and analyze the percentage of real-world patients that would not fulfill each of these criteria. The vast amount of electronic data also presents unprecedented opportunity for improving trial design with big data technologies. A visual analysis tool of quantitative eligibility features named VITTA (http://is.gd/VITTA), which includes processed studies summaries in ClinicalTrials.gov, allows one to flexibly select trials in the same disease domain and then visualize their study populations with a quantitative eligibility feature6. For example, VITTA can visualize overly included or systematically excluded value ranges of HbA1c of type 2 diabetes trials. Milians and her colleagues used semantic web technologies to structure eligibility criteria to enhance their reuse and relaxation7.

The underrepresentation of older adults in clinical trials reduces their generalizability and the cost-effectiveness ratio. Concerted efforts should be made to attract older adults who are safe to be enrolled in the trials on medical conditions often seen in older adults. Clinical trials with optimized balance between internal validity and external validity will give their findings more credibility.

References

1. Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Jr., Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(27):2061-7. PMID: 10615079

2. Schoenmaker N, Van Gool WA. The age gap between patients in clinical studies and in the general population: a pitfall for dementia research. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(10):627-30. PMID: 15380160

3. van de Water W, Kiderlen M, Bastiaannet E, Siesling S, Westendorp RG, van de Velde CJ, et al. External validity of a trial comprised of elderly patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(4):dju05. PMID: 24647464

4. Wysowski DK, Swartz L. Adverse drug event surveillance and drug withdrawals in the United States, 1969-2002: the importance of reporting suspected reactions. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(12):1363-9. PMID: 15983284

5. Hudson KL, Lauer MS, Collins FS. Toward a New Era of Trust and Transparency in Clinical Trials. JAMA. 2016;316(13):1353-4

6. He Z, Carini S, Sim I, Weng C. Visual aggregate analysis of eligibility features of clinical trials. J Biomed Inform. 2015;54:241-55

7. Milian K, Hoekstra R, Bucur A, Ten Teije A, van Harmelen F, Paulissen J. Enhancing reuse of structured eligibility criteria and supporting their relaxation. J Biomed Inform. 2015;56:205-19