Osteosarcopenic obesity as a new syndrome in elderly: What are the prevention and management challenges?

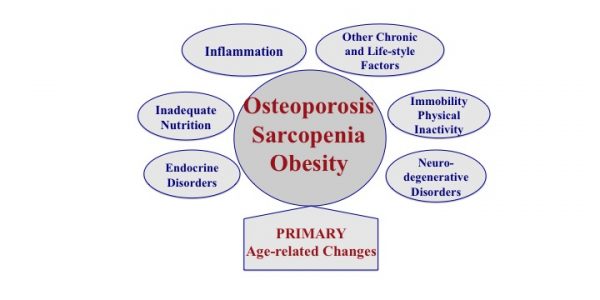

The triad of bone, muscle and fat tissue deregulation: Recently, a new syndrome was identified and termed osteosarcopenic obesity (OSO), signifying the impairment of bone, muscle and adipose tissues as an ultimate consequence of aging. OSO may also develop due to the initiating presence of overweight/obesity perpetuated by low-grade chronic inflammation, as well as to inadequate diet and lifestyle.

Additionally, some chronic conditions, like cancers, diabetes and other diseases that cause endocrine imbalance and stem cell lineage disruption may also cause OSO. While the close relationship between bone and muscle has been increasingly recognized in recent years, the role of fat tissue—whether as overt obesity, age-related fat redistribution, or fat infiltration into bone and muscle—is only beginning to receive more attention in the context of bone and muscle impairments. We realize now that obesity (once thought to be protective of bone and muscle), is increasingly linked to deterioration of these tissues, especially with aging. Therefore, other new terms; osteopenic obesity and sarcopenic obesity, resulting from increased overall body fat and/or fat infiltration into bone and muscle, leading to lower bone and muscle mass, quality, and possibly increased frailty, need to be taken into consideration as well.

Currently, there are no estimates about the number/percentage of older adults suffering from the combined condition of OSO and some preliminary criteria to diagnose it are just being developed. However, at least 54 million Americans currently have osteopenia and/or osteoporosis and one in two American women will experience a bone fracture. Additionally, about 5-13% of adults >65 years old and ~50% of adults >80 years old have sarcopenia. Ironically, hip or any other osteoporotic fracture accelerates the onset of sarcopenia in older adults; and sarcopenia, which impairs overall physical function, increases the risk of falls and fractures. One of the most common health problems in the osteosarcopenic obese population is increased risk of falls and fractures. Fall-related injuries are one of the major causes of mortality and morbidity among the elderly. These injuries could have a significant impact on health-related costs and quality of life. In 2014, one third of fall- related deaths were attributable to osteoporosis and/or sarcopenia.

The economic impact of third component of OSO (overweight/obesity) is especially manifested in healthcare costs and long-term loss of productivity. The annual medical costs for an obese individual are on average $1,429 higher than that of a normal-weight healthy individual. The recent rise in the prevalence of obesity is associated with comorbidities such as type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, stroke, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, renal failure, cancer and others. Aside from all of these complications, obesity has been associated with a 6 to 20-year loss in life expectancy.

Management: Although chronic disease, drug therapy, genetic predisposition and environmental factors are the main determinants in the etiology of OSO, lifestyle factors such as dietary patterns and physical activity are important as well. The latter two play a substantial role in metabolic homeostasis, determining to what extent an individual is able to preserve bone mass, muscle mass, and overall function, while still preserving an optimal body weight or reducing obesity with age.

Nutrition: Although American adults consume more food and total energy than people of many other cultures worldwide, evidence points to increased malnutrition risk with age and a link between the so called “Western-type Diet” and development of chronic disease, including bone, muscle and fat tissue disorders. Older adults in the United States are potentially at nutritional risk due to three main factors: increased consumption of high-energy and low-nutrient-density types of food; inadequate dietary fiber consumption; and decreased ability to absorb or utilize some essential nutrients with age. The Western Diet being heavily based on processed food, provides increased energy but decreased amount of many essential nutrients, and promotes deregulation of major systems in the body. A typically low dietary fiber intake in older adults is associated with insulin resistance and increased inflammation, especially in the obese. Western diet is also characterized by the high ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (the latter being eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)), which contributes to low-grade chronic inflammation and other unfavorable physiological outcomes. Besides the relatively unwholesome diet, older adults often consume less nutrients secondary to decreased appetite, side effects from medications, dementia or a desire for weight loss. Particularly affected nutrients are protein, calcium, magnesium and vitamin D, all needed to maintain and build bone and muscle. Additionally, dietary absorption of most of vitamins and minerals is also decreased, making it harder for the body to utilize them from the food consumed.

The combination of low protein, high simple carbohydrates, deficiencies of calcium, magnesium and potassium and excess of phosphorus, sodium and iron may be associated with lower bone mass, sarcopenia and obesity, and therefore OSO syndrome. Overall the nutrient composition of the Western Diet, distribution and amounts, for both macro and micro nutrients may not promote healthy aging and may be contributing to the development of OSO syndrome.

Physical activity: In general, physical activity is needed for maintenance and improvement of all components of body composition, as well as the physiological and mental health in people of all ages. Specifically for the OSO syndrome, physical activity, even in the form of low intensity or habitual activity, is needed to maintain or improve bone health, muscle strength and quality, improve balance, and reduce adiposity and inflammation, with aging. A comprehensive exercise program for older adults includes aerobic, strength, flexibility, and balance training and could reduce risk for falls, increase functional ability, and improve quality of life. However, recent findings show that although resistance training may increase lean (muscle) mass and weight bearing exercise may result in a reduction of the rate of bone loss (rather than in a significant increase in bone mass), the best exercise is what an older person is able to do. Aside from some medium to high-impact activities, habitual and low-impact physical activity including heavy housework, gardening, do-it-yourself activities, recreational activities and walking have been shown to be beneficial for bone, muscle and overall endurance.

Other alternative exercises such as Tai Chi, Yoga, and Pilates, could be used to support body composition and prevent bone loss and, as it has been shown, these exercises are associated with increased quality of life of older individuals. Overall, older adults may require special considerations such as tailoring progression of exercise intensity and beginning at a lower intensity. However, any type of immobilization, even during illness, should be avoided as much as possible in order for the proper maintenance of bone, muscle and fat tissues.

Conclusions and overall recommendations: OSO syndrome is a multifactorial condition of age-related changes in body composition including bone loss and muscle loss combined with increased adiposity. This complex condition of aging may be aggravated by poor nutrition, lack of physical activity and chronic disease. Treatment for OSO syndrome or its management may require the combination of healthy/optimal nutrition and different modes of physical activity. For the best prevention, efforts should be made to achieve peak bone mass before the age of 30, to gain/maintain muscle mass for all age groups and maintain healthy weight. As discussed above, nutritional interventions include: consumption of foods with high and good quality protein (eggs, fish, meat, dairy) adequate energy intake (to maintain healthy weight), adequate calcium, magnesium and vitamin D intake (dairy foods), consumption of food rich in EPA and DHA (omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids; as found in flaxseed oil, fish oil, walnuts, soybeans). Moreover, physical activity including strength training and aerobic exercise supports the maintenance of bone and skeletal muscle mass and thus attenuates osteopenia/osteoporosis as well as sarcopenia and may maintain weight. However, habitual daily activity as well as some alternative types of exercise (Yoga, Pilates) may be more acceptable in older individuals and thus better suited for the prevention and management of OSO syndrome.